Why I Became an Entrepreneur

I’ve run my own business for over a decade, writing and selling books and courses. In the beginning, it was just me. For the last few years, I’ve had a small team.

When I see people promoting entrepreneurship, the reasons for it are usually simple: more money, greater freedom, no boss.

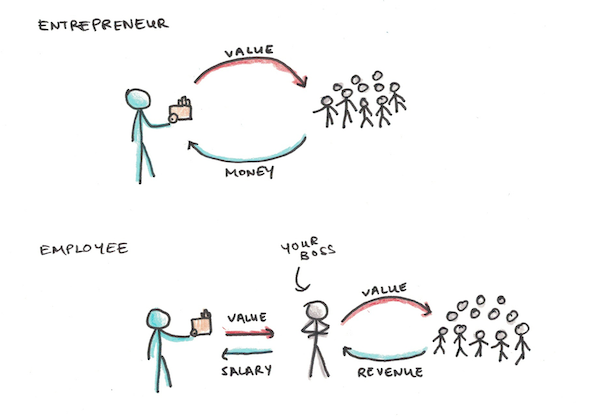

But for me, the biggest draw to running a business was the pure meritocracy of it. If you can sell stuff, you make money. If you can’t, too bad.

Few professions are so directly tied to results. Even if you’re a great worker, your value is filtered through the perception of your boss, your colleagues and office politics. Academics need grants, tenure and peer approval. A programmer might be ten times as productive as his peers, but probably won’t get paid ten times as much (the other workers might think it unfair).

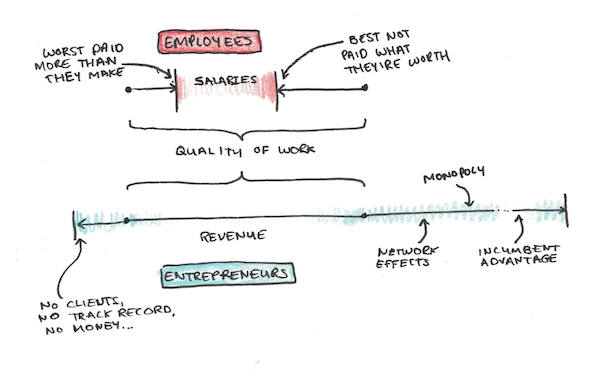

Incomes in most professions are compressed. Superstar employees tend to get paid less than they’re actually worth—because what they’re actually worth is often obscene. At the same time, duds can often chug along, collecting a paycheck despite producing little value.

Entrepreneurship, ideally, doesn’t have these social niceties. I remember my first month earning any money at all from my business, after having worked at it for months—I made less than fifty bucks from AdSense revenue. I’ve also had friends that have individually earned over a million dollars in a single day.

Our egalitarian instincts often recoil at these extremes. Forty dollars is not enough to live. Nobody needs millions. But these outcomes are simply the aggregation of people individually choosing whether or not to buy your stuff or visit your website.

The Reality of Entrepreneurship

That was the dream, at least. In reality, entrepreneurship has many of the same popularity contests, politics and patronage that many other forms of work do. Did someone high-profile recommend your business? That alone can put you back in the black.

While employees tend to experience income compression, entrepreneurs often experience income stretching. Many of the business processes are little engines of expontential growth. Winners take all and to each who has more is given.

Yet, despite these deviations from the ideal, I still think starting a business tends to be better on these fronts than most other types of work.

True, popularity and who-you-know continue to matter in business, just as they do in work. But, at the end of the day, you’re always tested by the market. If you can make customers happy, you’ll attract allies, investors, partners and promoters. If you can’t, not even friends in the highest of places can help.

Similarly, while income stretching is clearly less desirable than income compression (your first $100 makes you much better off than your ten-thousandth), if you can make it work, you’ve really earned it. You know that pity or pride wasn’t a factor.

High-N and Low-N Professions

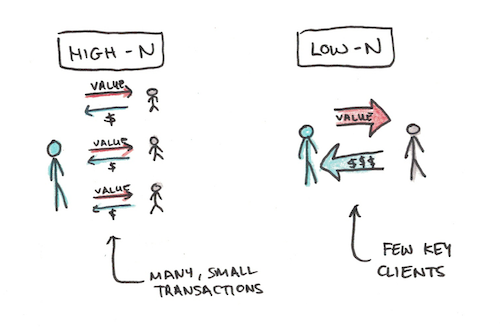

The main difference, to me, between running (most) businesses and working (most) jobs, is the number of people who need to like you in order for you to thrive.

In a business, you will have thousands of customers. In a job, you typically have only one (your boss). If one person doesn’t like you, that’s their problem; if everybody doesn’t like you, that’s your problem. The more people you have to serve, the more their decisions will converge to the true value. If you only have a couple people to please, there’s a lot more variance.

Having a lot of people to please also mutes the effect of individual politicking. When there are only a few key people to make happy, there’s a greater benefit of doing things unrelated to the work to reach that outcome. Sucking up to the boss, gossiping about rivals and forming coalitions are all common in typical jobs, but happen much less when you start a business. There are simply too many people to keep happy for this to be an effective strategy. You’re better off just making a really good product.

This also explains why different types of entrepreneurship exhibit this to different degrees. Solopreneurs who sell to consumers are one extreme—they interact with a large number of customers. In this setting, it’s easy to forget that you’re selling to actual people and not simply running a mechanical system. Seeing your customers as cogs in a machine isn’t good for business, but that it can happen at all is a testament to the relative lack of personal considerations swaying outcomes that reign in other areas of work.

On the other hand, you have businesses with few customers (think defense contractors) or fundraising stages where appealing to a handful of investors can make or break your company. Fewer patrons means success depends on more things than simply doing a good job.

Some jobs, in contrast, may be more like entrepreneurship for the same reason. Although academia has areas which require approval from a narrow set of peers (getting your PhD requires pleasing your advisor, getting hired requires a department to pick you), much of the overall success you experience is organic—do other people want to cite your work?

Some jobs, by the ease of measuring key results, also are more like running a business. Freelance writers online are evaluated on the ability to bring readers to a website. Salespeople earn commissions on the amount of product they move. This, too, shifts the work to be more like high-n professions because the boss can’t argue with results.

Would You Rather Be Judged by a Person, or a System?

Most people want the same things. To be loved, happy, safe and fulfilled. We’re far more alike than we are different.

Therefore, I think it’s interesting when you have a motivation that seems to point in the opposite direction of most people. I suspect this is the case with me.

Most people would much rather be judged by a person, and not a system. They want their crimes punished by judges and juries, not strict interpretations of the law. They want their college to admit students based on the “whole person” not simply who scored the highest score on the SAT. They want to be paid what they think they’re worth, not whatever people will pay for what they produce.

I tend to lean in the opposite direction. I think the outcomes of systems tend to be fairer than those judged by a few people in charge. People can be generous, yes. But they also tend to be petty, jealous, nepotistic and prejudiced. “Do people want to buy your stuff?” is, in my mind, a more objective question than, “Do you really deserve a raise?”

This isn’t to say the outcomes produced by systems are always ideal for society. I’m happy to pay taxes when I win to help out those who could not. But, at the same time, I’d prefer that the benefits go to help others via simple rules, not merely whomever lobbied or yelled the most.

This is why I’m always baffled at critiques of society being too mechanical and system-like. I feel the opposite! The world is run, too often, by prejudice, bias, tribal loyalty and patronage. A system isn’t guaranteed to be fair, but I’ll take it over the ad-hoc judgement of a few people in charge any day.

Entrepreneurship isn’t right for everyone. It’s probably not right for most people. It probably won’t make you more money, give more freedom or be more prestigious than just getting a good job would. But, if you want what you earn to be based on what you can make, it might be right for you.

The post Why I Became an Entrepreneur appeared first on Scott H Young.

Comments

Post a Comment